"What About Digital...."

Essay

by Ron Wisner

Digital, Digital, Digital. How many articles have you read about the New Wave of the Future. This writer has some awareness of his own partisan prospective regarding this issue. Like the Hawk in politics who can make peace with the enemy, I believe I can, at arms length, make peace with this camp and its child and provide a balanced and positive affirmation of both media. I do acknowledge my own vested interest. After all, I make cameras that are from the technological revolution of the last century. But, like the patron seated at a restaurant with friends, I eye with curiosity the dishes on other plates.

And why shouldn't I? What a fuss has been made. It is the solution to our problems, it makes our jobs easier in publishing and reproduction and manipulation.

Until last year, all of my own suppositions were strictly theoretical. Have you taken the plunge yet? Buy the big computer with all the memory, get into the windows based software, buy the scanner.

Until last year I had the purity and authority of a teetotaler promulgating prohibition. During the past few years, I have been asked my opinion about digital imaging, and doubtless my the interrogators were expecting partisan intransigence.

My argument must be one of historical perspective. Looking backward to each proceeding invention, style or medium, whether it be lithography, etching, woodcuts or the like will give good grist for this argument.

Consider, for instance, the turn of the century, a time when Alfred Stieglitz debated and defended photography as an art: "Photography as a fad is well-nigh on its last legs, thanks principally to the bicycle craze. Those seriously interested in its advancement do not look upon this state of affairs as a misfortune, but as a disguised blessing, inasmuch as photography had been classed as a sport by nearly all of those who deserted its ranks and fled to the present idol, the bicycle. The only persons who seem to look upon this turn of affairs as entirely unwelcome are those engaged in manufacturing as selling photographic goods." (Alfred Stieglitz, 1897, The Hand Camera- Its Present Importance)

Substitute "computer" for "bicycle". Remember, that in this arena of the photo magazine, we regard the computer as an alternative imaging system, but to the general population it is, like the bicycle of one hundred years ago, a commodity which competes for attention, hobby time, disposable dollars, and more than the bicycle, a capital investment for businesses.

Stieglitz was not just describing a new medium and its fancy with the general public. He was a proponent of photography as an art form. It is the art form, at that time feared by him lost to the public as sport, which has been the center of debate for over one hundred years now.

Stieglitz's argument has a peculiarly familiar ring today. As the society progresses inexorably toward the ever more sanitized photographic process, the public has lost its ability to take a light reading, to set an aperture, to focus a lens and even to load the film or hold the camera still (as in the case of the video medium), all skills taken for granted by the photographing public of one hundred years ago.

And of course, the public has been trained by the ever spiraling process of miniaturization to accept ever worsening quality. Remember the horrible, grainy prints which spewed forth from the disc camera? It seems that even the masterminds of the monolithic corporate purveyors failed to anticipate the public's unwillingness to sink to such abyssal depths of quality.

I may sound strident, but honestly, I am not. None of the forgoing is relevant to photography as art, because clearly snapshots of Aunt Matilda by the public are not nor are they intended to be art. If John Q Public calls himself an artist, intends to make art of Aunt Matilda, and hangs the image in a gallery (virtual or otherwise), then maybe it is art, but that is another philosophical discussion.

It must be obvious that the debate surrounding the legitimate place of digital verses traditional photography must lie in the dilemma which started the debate so long ago. Does photography not have its practical, utilitarian manifestations? Does this fact negate the use of photography, as art, to express the human soul?

To photograph Aunt Matilda, or to record a news event, to photograph a product or place, is a function as practical as the painted portrait of the last and proceeding centuries. So too was the making of a lithograph, an etching or woodcut of the last century. The artisans of those media would not usually have been referred to as artists, but as master-craftsmen whose skills might mimic art, and whose intentions are were clearly exigent and subordinate to reproduction.*

Speaking of functional, the concerns of today's photographers and their resistance to the digital wave usually is expressed as an argument pointing out all the functional difficencies of digital state-of-the-art. Though they miss the point regarding the bigger questions of art and expression, there are some real concerns which will dictate the econimic viability of the two media. And we must indeed remember that choose what one will, economics will determine which will be available in the long run, and in what form.

The "old" analog method comes with a simple array of equipment, and at a much lower cost, initially. The camera and lens is simple enough, at least in the case of large format photography, and film, at least for the user, is simple, though it belies the century of physics and chemical engineering which went into its develpement.

On the other hand, the desire to make high quality images using the digital process is tantamount to commiting to a significant bank loan. High resolution drum scanners, gigabytes of memory, display screens sufficient to manipulate the image charactoristics and see the real results, and then output devices such as film or Iris printers are all a necessity. And once you have bought said equipment, it is aready obsolete.

And speaking of equipment, how many large format phtographers do you know who are obsessed by the weight of thier equipment? To photograph with digital in the field means more wieght and more "stuff": power supply, cable, storage device or a computer with a hard drive, plus your camera and tripod and all the other gear you would ordinarily bring.

As for other practical concerns, time is money and it takes time to make a digital image. In the studio it can take many minutes, and the flash equipment which most pros have in thier arsenal is useless. Now one must go back to Hurell-like hot lighting, or preferably special HMI daylight balanced lights, since the scanners and ccd chips are balanced for daylight.

To further compicate things, disproportionateley bright objects such as bare bulbs or specular highlights "burn-in" on scanners and leave streaks all the way across the image. And forget about low level lighting which is so often the subject of art phtographers. Want to take an existing light, high resolution scan of a street scene at night? Forget it. The old way is the only way.

To be sure, the digital process has completely taken over the publishing industry. Want a giant enlarger cheap? Go to your nearest printer and make an offer for his old process camera. I got my 25x25 Robertson for $300. Virtually all but the biggest offset-printed reproductions, including magazines, catalogs ad infinitum, pass through the digital process before they go to press. When I send an add to this magazine, I send a disk. I have even emailed it! I have scanned the image (usually from a Polaroid), composed the add in my computer and sent the whole thing ready to go on film.

On the other hand, "if quick and dirty" digital images for use on the sreen or the internet are your goal, then one of the low cost digital cameras already on the market is a very practical tool, and will save alot of time and film. Most of our readers and customers, however, are into the craft of a fine, high resolution image, so both capabilities may exist concurrently within thier repertior.*

Interesting, that we place much emphasis today on the "craft" of photography. Nor does this craftsmanship necessarily define photography as art any more than in the above cited case [of old masters using old processes of painting or etching for the purpose of reproduction.] Stieglitz would reject much of today's photographic craft, as fine technically as it may be, as "technically perfect, pictorially rotten."

There is a dilemma here. The dilema is that of recognizing and valuing the thing verses the expression. In the inexorable march toward the hands-off society in which we have virtual art to go with virtual reality and virtual mail, the product of human hands is more and more revered. The delineation between the fine arts as a "roll up your sleeves and get your fingernails dirty" and the "you push the button, we do the rest" is coming to its "virtual", logical, ever more unbreachable and irrevocable development. The photographic elite will be the craftsmen who know and use the ancient materials. It has already started. Never before has there been such interest among amateurs in large formats, forgotten formulas and arcane processes, even as the numbers of large format professionals dwindles every year. Witness the rebirth of platinum paper as a commercial commodity.

Thus, the thing itself, to hold and cherish is the art object, and this object has a value in its manifest existence, independent of its artistic merit. A vintage print by a known artist, as any gallery owner will tell you, is much more valuable as an object than a print of far greater artistic merit by a contemporary unknown. The vintage print, as an object, has value. The vintage print, like the contemporary print, both share an essential quality. They were both handled by the artist. With his own hands he made the object, and then passed it on to other hands, and with it conveyed a singular existence which can only beheld by one person at a time.

The dilemma, then, keeps coming back, like it or not, to the perenial question of art and the definition of art. Is the object a superb (hopefully) embodiment of a superb artistic expression? Why can not any medium be such an expression of an artistic thought? Why not digital?

To further complicate this discussion one need only cite the intrinsic part the medium itself plays in the expression. Although Ansel Adams once said he would quit photography if it ceased to fulfill his expression, he certainly chose photography for the unique way in which it suited his expressive needs. If Marc Chegal executed his images in pastels rather than his famous stained glass, would not this completely change his expressive intent. What about the texture and appliqued nature of Miro's paintings. Clearly "craft" embodied in the art object is intertwined with art in both of these cases. Suppose he had decided on the digital image as more suitable to his needs?

To understand the digital, virtual creation as legitimate art I have considered my own activities as a composer as an example. When I write music these days, rather than use pencil and paper as I was originally trained, I am using a computer. It looks like a sheet of music on the computer screen, and I use the mouse to place the notes on the page. I can push a button and it will play back instantly. I have a string quartet, or even a full orchestra at my disposal at the click of a mouse. It doesn't really sound like a string quartet but it's close enough. I do not consider it the final realization of my music, which is concieved for real string players. And there's the rub. Many composers revel in the

synthesized sounds of the computer and those sounds are essential to their expression. The sounds are as much a part of the composition as Mozart's use of horns or strings or woodwinds.

Why wouldn't digital images, conceived as floating, mass medium, synthesized objects, be just as valid in their genesis as synthesized music? The synthesizer has been with us for more than twenty years. The technology of the digital image and the public's access to it is just a little slower in coming.

The concept of art, therefore, may or may not be separable from the object itself. Last year I attended a panel discussion at the photographic convention in New York, hosted by Polaroid, on the state of Digital imaging. I was fascinated to find that, while the panel was well aware of the mass conveyability of their art, which, as they saw it, resulted in the democratization of the art image, they did fail to recognized the value of the object created by the artist. There was much discussion of and against the object and the Museums where such objects reside, which were maligned as "repositories for frozen egos."

If the "revolution" of the computer results in a whole new medium, it does not take anything away from the more traditional photographic process. It may actually elevate, finally, once and for all, photography as a fine art. It will certainly keep alive, and possibly muddle, the debate about what real art is, and it may lend false credence to practitioners of fine photographic craft as artists when it is not deserved, in the same way in which anyone who picks up a brush and paints a painting may pronounce himself an artist. Contrary to the protests of the sometimes angry digital camp, who have sought refuge in digitally broadcast images as a result of the lack of thier own personal recognition, the final arbiter of this judgment about who is an artist and who is not is the very winnowing process provided by those "elitist" museum repositories, or even magazines such as this one, which put the image to the test and review of one's piers. Digital imaging is just one more medium both for self expression and as a tool for practical image making, and will take its rightful place along side other media.

Compiled and edited for the WWW - Essay by Ron Wisner, Ceo Wisner mfg, Marion, USA.

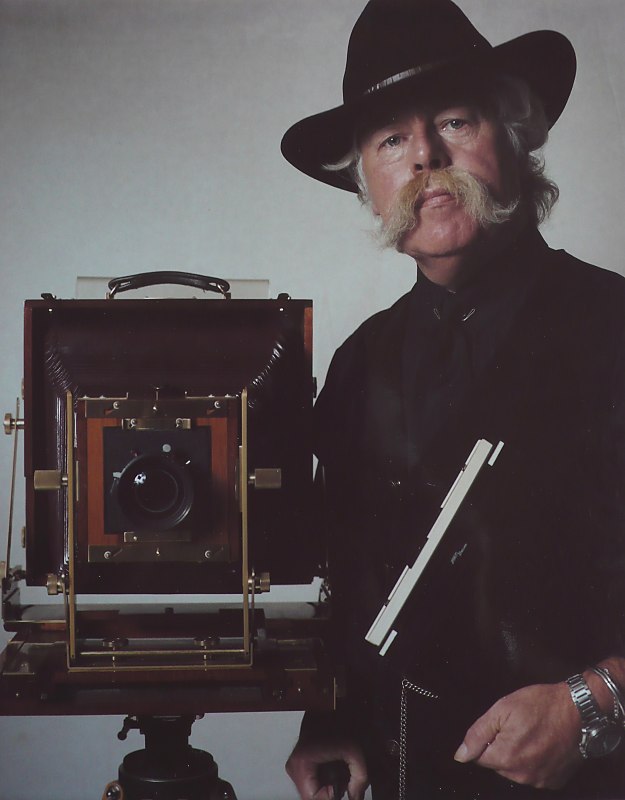

Auto portrait on 8x10 Polaroid "Author John D. esq and the Wisner Technical Field 8x10" Whois Johndesq Close

![]()